Booking is now open for this free one day workshop, “(Re)thinking Protest Camps: governance, spatiality, affect and media” to be held on Tuesday 26 June 2012 at the University of Leicester, UK. Instructions and an online form to reserve a place are provided below.

Workshop Programme and Reading

The (Re)Thinking Protest Camps Workshop is structured around four ways of approaching protest camps and theorizing their social, cultural and political impact. Following short introductions by discussion leaders, in each of our themed sessions, workshop participants will be invited to collectively examine the governance, spatialities, affective terrain, and media representations of/from protest camps. The day aims to provide plentiful opportunity for open, yet focused, discussion and debate, as well as a space for networking and research community building.

Schedule

09:30-10:00 Registration

Coffee & Tea

10.00-10.15 Welcome & Introduction

10.15-11.15 Opening Lecture: Sasha Roseneil

After the camp – what do we leave behind? Legacies, memories, transformations?

Sasha Roseneil is Professor of Sociology and Social Theory and Director of the Birkbeck Institute for Social Research, at Birkbeck, University of London. She has written extensively about Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, and more widely about social movements, feminist politics and intimacy and personal life.

Reading:

Disarming Patriarchy: Feminism and Political Action at Greenham, 224pp, Buckingham, Open University Press, 1995.

Common Women, Uncommon Practices: The Queer Feminisms of Greenham, 329pp, London, Cassell Academic Press, 2000.

‘Greenham Revisited: Researching Myself and My Sisters’ in D. Hobbs and T. May (eds) Interpreting the Field, pp. 177-208, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993.

Break 11.15

11.30-12.15 Session 1: Spatialities

Discussion led by: Jenny Pickerill & Gavin Brown

This session examines protest camps spatially. It considers the physical space occupied by camps (in their locational context), their materiality, and the spatial practices that occur within/through those sites. It interrogates the (strategic) location of encampments and their (non)relations with the objects of their protests. It debates the place of protest camps in cohering social movements at different scales, by providing spaces in which those movements can converge, but also hubs through which different types of networks are articulated across varying distances and of different durations.

Break 12.15

12.30-13.15 Session 2: Governance and Organisation

Discussion led by: Fabian Frenzel & Keir Milburn

Protest Camps are sites of experimentation with alternative forms of organisation and governance. They are places where radically democratic models of decision making, as well as decentralised, autonomous structures are tested and developed. As an organisational form, protest camps invite the practice of prefigurative politics (Breines 1989). The experience of many protest camps proves the use and utility of these alternative forms of governance, yet also shows clear limits of such attempts, for example when protest camps reproduce divisions of gender, race and class rather than work to overcome them. This session addresses the possibilities of and limitations to autonomy in protest camp organisation and the learning processes that may result from tackling these limits.

Reading:

Cornell, A. (2009) ‘Anarchism and the Movement for a New Society: Direct Action and Prefigurative Community in the 1970s and 80s’ online http://www.anarchiststudies.org/node/292

Frenzel, F (2010) ‘Exit the system: Crafting the place of protest camps between antagonism and exception’ online at: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/15924/

Lang, S. and Schneider F. (2002) ‘The dark side of camping’

online at http://www.all4all.org/2004/07/985.shtml

13.15-14.15 Lunch

14.15-15.00 Session 3: Affect

Discussion led by: Anna Feigenbaum, Emma Dowling & Anja Kanngieser

What does it mean for politics to be attentive to the affective dimensions of protest and encampment?. Affect is defined by in a number of different ways, most of which relate to our pre-linguistic feelings and sensations. Affect theorists are often concerned with the materialities of daily life as they shape bodily reactions and responses, moving us toward, as well as potentially alienating us from each other. In this session we raise questions such as: How does affect accumulate and circulate in protest camps, shaping practices and policies? How does affective labour take shape in protest camps, intersecting with lived conditions of race, class, sexuality and gender? How do the affective qualities of the voice engage people’s capacities to listen and to respond to one another both in meeting spaces, as well as in daily interactions?

Reading

Trott, B. (2007): Notes on Why It Matters that Heiligendamm Felt Like Winning, http://transform.eipcp.net/correspondence/1183458348#redir

Free Association: Moments of Excess, either online: http://freelyassociating.org/moments-of-excess/moments-of-excess-2006/ or the book (published by PM Press)

Shukaitis, S. : Questions for Aeffective Resistance, from his book Imaginal Machines, the chapter is downloadable here: http://f.cl.ly/items/3E1a1X2b0A0M3u0p2x15/Shukaitis%20-%20Questions%20for%20Aeffective%20Resistance.pdf

Break 15.00

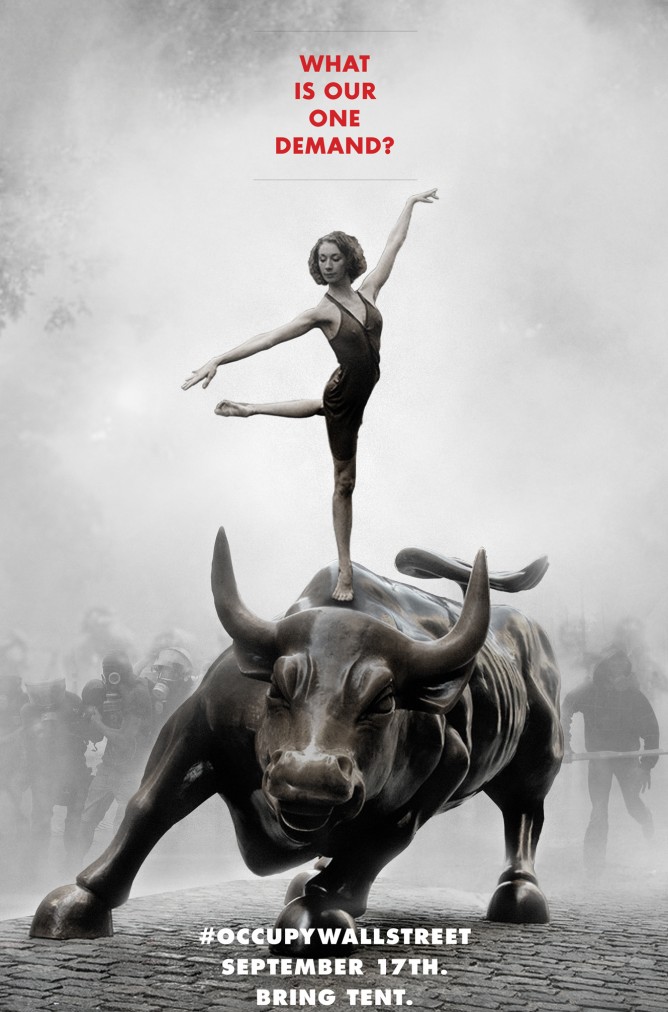

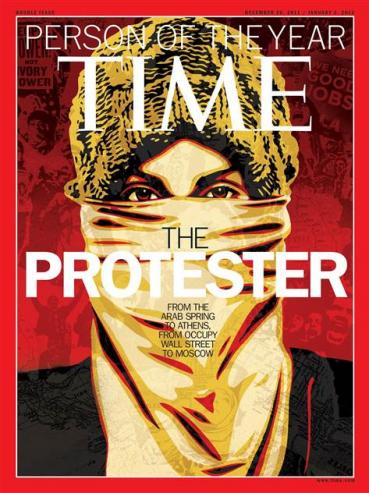

15.15-16.00 Session 4: Media Representation & Cultural Production

Discussion led by: Patrick McCurdy & Julie Uldam

Media is a site of struggle on par and in tandem with physical places of resistance. As such, the representation of a social movements or protest camps in both mainstream and social movement-produced media can have a powerful impact on its public standing and success. Recognising that media – in all its forms – serve as an important environment and platform for social struggle, this session is interested in the representational strategies of protest camps and will debate how, and to what end, media (mainstream, movement and social) are used in such spaces.

Reading:

1. Castells, Manuel (2007). “Power and Counter-power in the Network Society”, International Journal of Communication, Volume 1. Available from: http://ijoc.org/ojs/index.php/ijoc/article/view/46/35 Article captures the core ideas of Castells’ 2009 book, Communication Power. The idea of counterpower is helpful for understanding the rise and media resistance of the Occupy movement.

2. Donson, Fiona, Graeme Chesters, Ian Welsh and Andrew Tickle (2004).“Rebels with a Cause, Folk Devils without a Panic: Press jingoism, policing tactics and anti-capitalist protest in London and Prague”, International Journal of Criminology. Available from: http://www.internetjournalofcriminology.com/Donson%20et%20al%20-%20Folkdevils.pdf

This study is based on Stanley Cohen’s idea of ‘folk devils’ which is a helpful lens for reflecting critically on the media’s coverage of the Occupy movement.

3. Gladwell, Malcolm (2010). “Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted”, The New Yorker¸ Available from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell A now famous polemic on the debate about the potential for social media to facilitate activism.

Break 16.00

16.15-17.15 Research network foundation

Facilitated discussion on future research collaborations and networking

Following the conclusion of the workshop there will be informal drinks and dinner at a restaurant near the train station for those wishing to attend.

If you planning to book your travel in advance, please consider the following approximate times for the end of each of those activities:

Workshop ends: 17.15

Drinks till about 18.15

Dinner from 18.30 to ….

(it’s about 20 mins walk from the university to the trainsation and 10 mins from where we have drinks and eat)

Workshop Overview

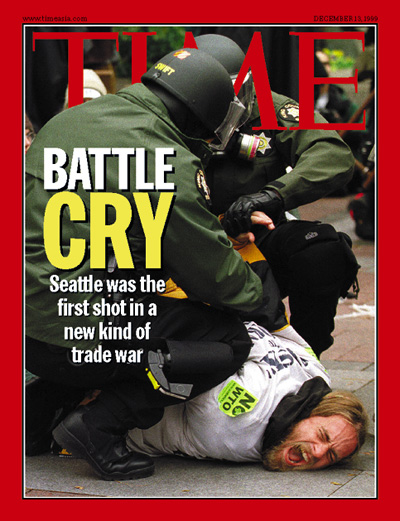

Over the last year, urban protest camps and encampments have captured the world’s attention and imagination. From Tahrir Square to the tent city of Tel Aviv, from the encampments of the Los Indignados in Spain to the Occupy movement, enduring protests have arisen to demand democracy and fight austerity measures. In addition to these protest camps situated within/outside symbolic targets, other kinds of protest camps have grown as a social movement tactic in recent decades.

These include camps that aim to prevent or disrupt the destruction of a site under social or environmental threat (for example, anti-roads protests, or the solidarity camp that sought to prevent the eviction of Irish Traveller families from their land at Dale Farm in Essex). There have been camps that draw attention to sites posing a specific social, military or environmental threat (for example, the siting of Climate Camps outside oil-fuelled power stations or peace camps outside military installations). Finally, camps have been organised as counter-summits or ‘convergence spaces’ (Routledge 2003) in opposition to strategic meetings of global political leaders.

This one-day workshop seeks to examine both these recent and contemporary expressions of protest camps, as well as to chart the historical geographies of protest encampments in earlier periods. The workshop is open to a broad interpretation of ‘protest camps’ from physical encampments where people live, through to the picket-lines of long-running industrial strikes. In some cases it is the act of camping, of being in place, that is central, in others it is the duration and creation of a persistent physical infrastructure of protest in situ.

The workshop is structured around four ways of approaching protest camps to theorise their social, cultural and political impact. Through four short introductions examining the governance, spatialities, affective terrain and media representations of/from these sites, we hope to provide plentiful opportunity for open, yet focused, discussion and debate.

Workshop Organisers

The “(Re)thinking Protest Camps” workshop is organised by: Gavin Brown, Fabian Frenzel and Jenny Pickerill, University of Leicester, Anna Feigenbaum, Richmond, the American International University in London, and Patrick McCurdy, University of Ottawa.

Workshop Logistics

Booking is now open for a one-day seminar on “(Re)thinking Protest Camps: governance, spatiality, affect and media”, University of Leicester, Tuesday 26 June 2012. The event is free, and lunch is provided: but a place must be reserved in advance. Please complete the online booking form to book your place.

A limited number of travel/accommodation bursaries are available for postgraduate / unwaged participants or people without access to funding for such activity which are available on a first come, first served basis. To request a bursary please contact Gavin Brown (gpb10 (at) le.ac.uk) specifying your status and (briefly) the reasons for your request.

There will be a meal available afterwards at your own cost.

Location: University of Leicester – 15 minute walk from Leicester rail station. http://www2.le.ac.uk/maps/campus-map

Accommodation: we would recommend Spindle Lodge:

http://www.spindlelodge.co.uk/

or you can find other options here.

www.booking.com/Leicester-Hotels

(If you are unsure about where is and isn’t convenient for the University campus, contact the organizers.) Please also inform us of any special requirements (eg. dietary, access etc.). We will do our best to address these.

At present there is a

At present there is a

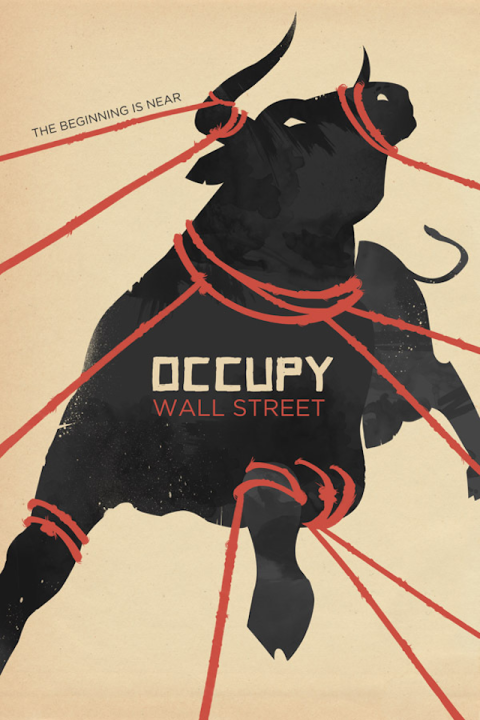

The Occupy movement was never about occupying a lawn or a sidewalk, but about occupying an idea. An idea which is dangerous. An idea which can be lost in the daily struggles of trying to keep a camp running. The evictions, including this weekend’s eviction of Occupy London have galvanized occupiers, provided a narrative and banner to organize under and bought time, to rescue its representation. Thus, Occupy can survive its representation and the evictions will help it do this.

The Occupy movement was never about occupying a lawn or a sidewalk, but about occupying an idea. An idea which is dangerous. An idea which can be lost in the daily struggles of trying to keep a camp running. The evictions, including this weekend’s eviction of Occupy London have galvanized occupiers, provided a narrative and banner to organize under and bought time, to rescue its representation. Thus, Occupy can survive its representation and the evictions will help it do this.

The vocabulary of occupation has recently gained a global political prominence for the Left. Those of us calling ourselves the ‘99%’, who – with varying degrees of radical fervour – broadly oppose ostentatious displays of capitalist wealth at the expense of general social welfare, have descended upon Wall Street and other urban financial districts to OCCUPY.

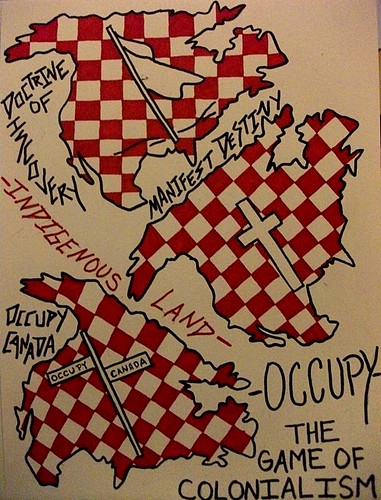

The vocabulary of occupation has recently gained a global political prominence for the Left. Those of us calling ourselves the ‘99%’, who – with varying degrees of radical fervour – broadly oppose ostentatious displays of capitalist wealth at the expense of general social welfare, have descended upon Wall Street and other urban financial districts to OCCUPY. Simpson spoke compellingly of 400 years of resistance by Indigenous people as the longest social movement in Canada, pre-dating Canada itself. As a result, the term occupation sounds, for Indigenous people, like political and cultural genocide. In light of this, she argues that we need to reject the language and ideology of conquest and colonialism entirely. Decolonisation needs to be at the centre of the movement. Simpson’s own experience of resistance was influenced by the Indigenous women in her community, whose love, commitment and strength made survival as resistance possible. She presented the Occupy movement with a challenge: make the concerns of Indigenous women central. This, she argued, would make the movement truly radical.

Simpson spoke compellingly of 400 years of resistance by Indigenous people as the longest social movement in Canada, pre-dating Canada itself. As a result, the term occupation sounds, for Indigenous people, like political and cultural genocide. In light of this, she argues that we need to reject the language and ideology of conquest and colonialism entirely. Decolonisation needs to be at the centre of the movement. Simpson’s own experience of resistance was influenced by the Indigenous women in her community, whose love, commitment and strength made survival as resistance possible. She presented the Occupy movement with a challenge: make the concerns of Indigenous women central. This, she argued, would make the movement truly radical. Upon making a few calls, they quickly learned the source: “Adbusters.” “Isn’t that some art magazine?,” someone asked. Footage from the occupation shortly emerged, revealing a large contingent of mostly middle class white youths. Thomas-Muller described his initial reaction as one of fear. He was afraid that the scenario could turn into one where various social movements would become alienated and dispersed. He feared that many of the participants were uneducated and unprepared, especially in terms of anti-racism training. He worried that they had already forfeited the crucial opportunity to move socially disadvantaged groups to the fore of the movement.

Upon making a few calls, they quickly learned the source: “Adbusters.” “Isn’t that some art magazine?,” someone asked. Footage from the occupation shortly emerged, revealing a large contingent of mostly middle class white youths. Thomas-Muller described his initial reaction as one of fear. He was afraid that the scenario could turn into one where various social movements would become alienated and dispersed. He feared that many of the participants were uneducated and unprepared, especially in terms of anti-racism training. He worried that they had already forfeited the crucial opportunity to move socially disadvantaged groups to the fore of the movement. Goldtooth insisted that a movement based upon principle was needed, in light of which certain crucial questions would emerge. Most importantly at this point: what is a process for outreach and inclusion of indigenous people? Is this merely a moment or is it a movement? The tactical frame of the movement is the 99% – but who, he asks, is represented by that number? The movement is popular and diverse and, as such, Goldtooth insists that we must have clear protocols for dialogue, which would encompass this diversity. This requires combatting internalized oppression as well, and acknowledging that the system we are fighting is adept at instilling a sense of disempowerment, paralysis and isolation.

Goldtooth insisted that a movement based upon principle was needed, in light of which certain crucial questions would emerge. Most importantly at this point: what is a process for outreach and inclusion of indigenous people? Is this merely a moment or is it a movement? The tactical frame of the movement is the 99% – but who, he asks, is represented by that number? The movement is popular and diverse and, as such, Goldtooth insists that we must have clear protocols for dialogue, which would encompass this diversity. This requires combatting internalized oppression as well, and acknowledging that the system we are fighting is adept at instilling a sense of disempowerment, paralysis and isolation.

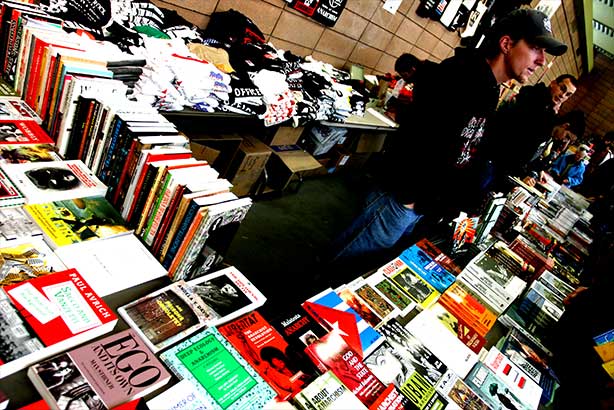

Patrick’s workshop Occupy! the Media will provide an introductory look into ideas of media framing and how the mainstream media has represented the Occupy! movement. It will also explore various innovations in the media strategies of different Occupy encampemnts from the use of uStream [

Patrick’s workshop Occupy! the Media will provide an introductory look into ideas of media framing and how the mainstream media has represented the Occupy! movement. It will also explore various innovations in the media strategies of different Occupy encampemnts from the use of uStream [

Before the Arab Spring, our work on the transnational history of protest camping was generally regarded as “too niche”, or “quirky activist stuff for idealists”. But by April 2011, as Tahrir Square became an international sign that perhaps another world was possible, the phenomenon of protest camping gained broader appeal. We were contacted that spring by a number of commissioning academic editors interested in the possibility of turning our on-going research into a book. After meeting with a handful of publishers, the choice to go with

Before the Arab Spring, our work on the transnational history of protest camping was generally regarded as “too niche”, or “quirky activist stuff for idealists”. But by April 2011, as Tahrir Square became an international sign that perhaps another world was possible, the phenomenon of protest camping gained broader appeal. We were contacted that spring by a number of commissioning academic editors interested in the possibility of turning our on-going research into a book. After meeting with a handful of publishers, the choice to go with