Exiting news: There is an opportunity for a funded PhD project on Protest Camps at the University of Leicester.

Description of the project

This PhD project will investigate forms of spatial organization in protest camps. It contributes a better understanding of spatialities of organization to the study of organizations. Spatial Organization consists of a range of organizational techniques in which territory, place and space are mobilized, employed and affirmed for organizational purposes. It differs from other types of organization, such as bureaucratic or contractual (market-based) organization. There is limited understanding how spatial and other types of organization interact, how they replace each other and what benefits and costs occur when they are employed. Understanding spatial organization matters because it allows making organization(s) more democratic and inclusive, helping those who organize to do so better.

In the project spatial organization will be investigated with an empirical study of protest camps, a form of alternative organization that has come to increasing attention in protest events since the Arab Spring in 2011. The existence of protest camps is widely regarded to benefit the protestors, at least in the initial period of a protest, by providing a permanent and highly visible presence in often symbolically charged public space. Protest Camps are highly pertinent to the study of spatial organization. Research has pointed to the way camps allow for protesters to mass-organize spatially, avoiding non-spatial forms of organization such as associations or unions, often understood by protest campers as excessively hierarchical and bureaucratic. Techniques of spatial organization in protest camps include the occupation and claiming of bounded territories and the building of infrastructures that aim to sustain life (housing and feeding protesters, etc) within the territory.

Camps show further elements of spatial organization, such as decentralization into living quarters or ‘neighborhoods’ as well as function areas such a ‘kids spaces’, ‘safe spaces’, libraries and places of worship, to name but a few. Protest camps’ active engagement in such practices of spatial organization have cohesive effects on the camp’s social and cultural fabric, building stronger camp communities. As a political act spatial organization also sometimes prefigures the political utopian aspirations of the protest campers in such a way that collaborative practices are learned, displayed and concept proofed in the camp. But can such aspirations be realized and maintained, in particular over longer periods of time? The study of protest camps in this project will give important new insights into the possibilities and limits of spatial organization.

Research questions:

- While spatial organization evidently has advantages for the protesters, what are the costs of spatial organization?

- How does spatial organisation relate to, complement, replace and improve other forms and techniques of organisation?

- How is the spatial organization experienced by and reflected on by protest campers?

Methodology:

Three empirical cases of recent protest camps will form the basis of a comparative study which considers different contexts: urban and rural, different political – legal environments, and different cultural settings. The research design is qualitative and empirically based on interview and documentary data. The prospective candidate will identify the specific cases in coordination with the supervisors.

The supervisors

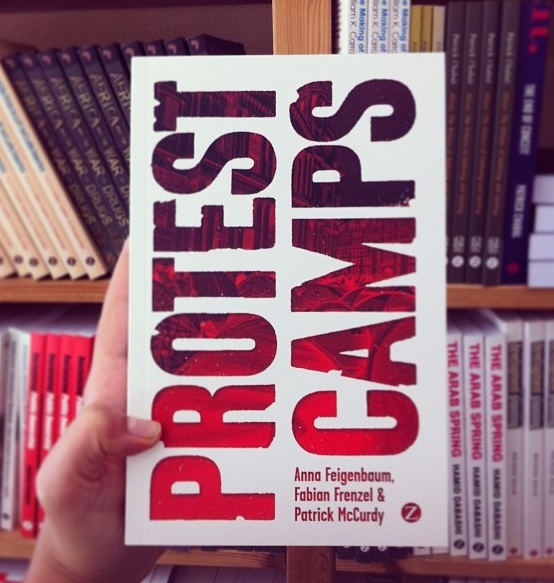

The supervisors have collaborated successfully since 2012 on the study of protest camps, most recently in a joint book editorship. Both bring unique sets of expertise into the project: Fabian Frenzel is an expert in the political economy of organization and has studied numerous protest camps empirically. Gavin Brown brings to the table a unique expertise in place based protests as well as theoretical and methodological tools for understanding socio-spatial relations and the role of spatiality in politics and subjectivity. The project will benefit the prospective student for its unique interdisciplinary perspective and the supervisors’ experience of working with each other.

Application

The studentship offers a Stipend at RCUK rates (£14,777 for 2018) and UK/EU fee waiver for 3 years.

International (non-EU) applicants are welcome to apply but must be able to fund the difference between the UK/EU and International tuition fees for the duration of their studies.

The deadline for applications is the 1st May 2018.

Full information on the scheme and how to apply

Please contact Fabian Frenzel ff48(at)le.ac.uk and Gavin Brown gpb10(at)le.ac.uk for any inquiries.