From July 2012-June 2013, Protest Camps Research Collective member Anna Feigenbaum examined the history of protest camps and knowledge exchange as a postdoctoral associate on the ‘Networks of Exchange’ project, hosted by the Rutgers Centre for Historical Analysis at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

- How do the circulation of people, objects, ideas and affect come to constitute new material formations of protest camps across time and place?

- How do, ideas and relationships arising from protest camp participation move nationally and internationally?

For this project I worked to develop our collective’s model for ‘infrastructural analysis’. We use the term ‘infrastructure’ to capture how protest campers build interrelated, operational structures. These structures come to function together, creating miniature societies able to disseminate information, distribute goods, plan actions and provide services (such as non-violence training, medical care and legal support). This infrastructural approach arises out of my previous research engagements with Actor-Network-Theory and builds on collaborations with Artivistic, Fuse Magazine and the Protest Camps Research Collective.

Why Infrastructures?

Attempts to chart neat alignments of ‘resource mobilization’ often misunderstand or misrecognize the micro-structures that facilitate and propagate social movement forms and ideas as they appear and disappear across cities, country sides and continents. Looking instead at infrastructures allows for an analysis of how people, ideas, objects and organising structures travel across time and space, becoming adopted and adapted as they circulate (Feigenbaum 2011; Frenzel, Feigenbaum and McCurdy forthcoming). Understanding the ways infrastructures travel and get reproduced can help pinpoint recurrent problems and evolve movement strategies. Some basic examples of these kinds of movements and exchanges between protest camps include:

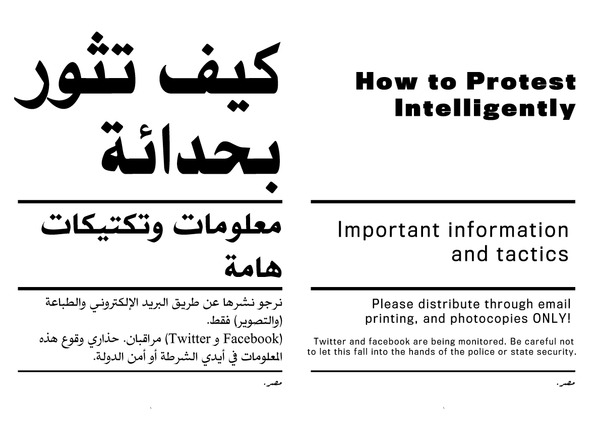

- Communication infrastructures: A logistical handbook from a 30,000 person nuclear power plant occupation in Germany in 1975 was used as the basis for information pamphlets circulated in the US two years later by the Clamshell Alliance.

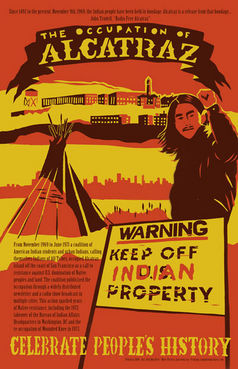

- Action infrastructures: The 19 month long Occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 by the American Indian Movement inspired resistance by protest campers at Minnehaha Free State in Minneapolis in 1998.

- Governance infrastructures: Argentinean forms of organising meetings in factories in 2001 got taken up in Spain in 2011 during the Real Democracy movement, and then became the basis for decision-making at Occupy Wall Street 4 months later.

- Re-creation infrastructures: A group calling themselves the ‘TAT Collective’ stored and delivered tents, marquees and kitchen supplies to protest camps around the UK throughout the 2000s.

In each of these cases a combination of people, technological objects and ideas were exchanged and adapted across time and place. These kinds of network exchanges help enable new protest camps to materialise—whether in the forests of Tasmania or the urban centres of Thailand.

In each of these cases a combination of people, technological objects and ideas were exchanged and adapted across time and place. These kinds of network exchanges help enable new protest camps to materialise—whether in the forests of Tasmania or the urban centres of Thailand.

Affective Networks

A less tangible, but equally important element of how protest campers exchange knowledge can be understood through the concept of affect. Our responses to images, ideas, technologies and other people involve both cognitive responses and feelings; or what can be called ‘affective responses’. Some affect theorists say that feelings are ‘sticky’ and when we encounter objects (whether material things, symbols or ideas) our feelings stick to them. When objects circulate through networks and become encountered repeatedly, they become stickier and stickier—laden with meaning and potent with feelings. As we encounter these objects we ‘orient’ ourselves to them: aligning, rejecting, attaching or disassociating ourselves from them. In other words, how we feel (or think-feel) in relation to objects gives shape to our politics (Ahmed 2004, 2010).

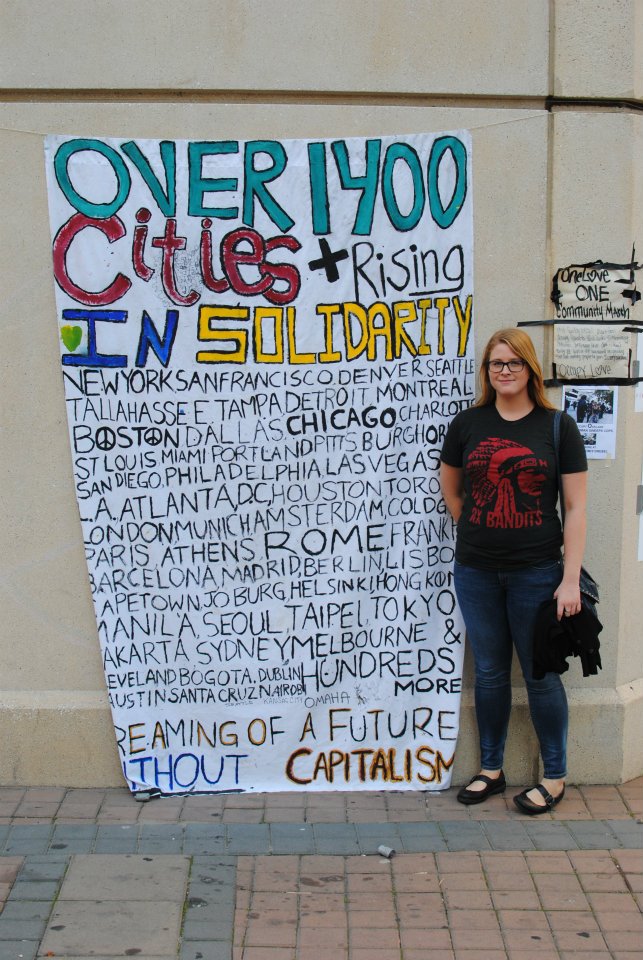

But people do not often think about politics as being made up of feelings in addition to positions and ideologies. Instead, social movement impacts are usually measured in the number of demands that get met, in the amount of new legislation passed, legal trails won, politicians elected or ousted. Yet these tools commonly used for sizing up both the success and the story of a protest are not able to understand the ways in which the circulation of feelings also forms connections and conflicts. These traditional measures cannot account for the convergences and divergences that grow between disparate groups struggling towards solidarity. They cannot pinpoint the winding networks and crooked exchanges that protest camps create, passing down stories and practices that shape social movements yet to come.

How to track a Network of Exchange

To gather empirical data around these kinds of networked exchanges (and exchange networks), I employ a combination of research methods, in addition to drawing on existing recorded histories of camps and their roles in social movements.

Archival Methods

Pamphlets, newletters, blog posts and related ephemeral artefacts offer rich insight into how physical and discursive political environments are shaped. Many archive materials contain traces of information such as notes and letters shared between people, announcements in meeting minutes, addresses on mailed items, and distribution lists.

Interview, Focus Groups & Participant-Observation

Interviews and focus groups also offer extensive insight into the organisational dynamics, political environments and everyday life of protest camps. Since January 2012 we have been travelling around to meet with protest campers as part of the ‘Campfire Chats’ workshop series. In addition, this project draws data from first-hand experience participating in and organising a range of protest camps spanning the past decade. This “insiders’ perspective” enables me to privilege those issues and voices commonly left out of mainstream reportage and top-down social movement scholarship.

These research engagements stand to shape the emergent area of protest camp studies, and contribute more broadly to the fields of Social Movement Studies, Science and Technology Studies and Communications.

For more information on the Protest Camps Network s of Exchange project, contact anna [at] protestcamps [dot] org.