“We have given the women a reasonable amount of time to make their protest, but they are trespassing and they must go.”

-Cyril Woodard, Chairman of the Recreation and Amenities Committee

Newbury Weekly News, Greenham, 21 Jan 1982

“Now is the time for the protesters, having made their point, to move on.”

-Mayor Boris Johnson, BBC News, Occupy LSX, 26 Oct 2011

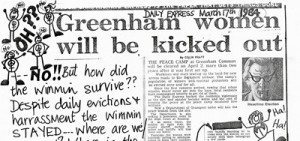

‘Time to Move On’ the headlines echo across thirty years. There is something eerily similar between this past call on protesters to pack up and the present justifications for an eviction of the OccupyLSX camp outside St. Paul’s Cathedral. Official press releases from St. Paul’s have been vague, citing safety concerns and insisting the Cathedral’s interests are not commercial . Yet this week canon chancellor Dr. Giles Fraser resigned over worries there may be “violence in the name of the church” and St Paul’s called on protesters to leave the site peacefully. Meetings amongst officials are currently taking place to plan legal action around removing the camp.

While the issues and parties at play here differ from past UK protest camps, the basic arguments remain the same. Occupy campers and their growing support network claim a right to peacefully protest. Those with commercial and political interests jeopardised by the continuing presence of the camp appeal to reasonableness and paternalistic concerns for safety in efforts to remove campers. Paving the way for an eviction, authorities rally public support by continually referring to protesters as dirty, clueless nuisances who should ‘get a real job’. An irony not lost on a camp that is, in part, protesting record high unemployment rates including 21% joblessness for 18-24s.

Back in the early 1980s at Greenham Common, protest campers became so used to this kind of name-calling, they would turn such insults into ditties with titles like ‘Brazen Hussies’ and the ‘Layabout Song.’ Although protesters are often painted with a brush of buffoonery, in reality the majority of campers and their supporters are very aware of how media representations operate and have a technological literacy that at times exceeds that of the journalists’ covering their encampment. As russell_collins joked on twitter earlier this week, “ @telegraph : If you’re having problems with your cameras on site, our tech team might be able to help!”

Between 1982 and 1985 Greenham Common campers were evicted so many times that most women lost count. Each time structures, food, art and personal belongings were cleared out, trampled and recklessly strewn around. If not rescued in time, items would be fed to a rubbish lorry campers came to call ‘the muncher.’ Yet, instead of moving on, women developed tactics to withstand repeated evictions. Wheels were attached to palettes holding tents and kitchens were made mobile. Sometimes women used yarn to weave together trees on the campsite, making it difficult for police and bailiffs to charge through the camp during evictions. Protesters’ support networks enabled rebuilding by sending more donations and showing encouragement. As one Greenham protester put it, they think we are a handful of women, but “we are 30,000 and there is no way to get rid of us.”

Anti-roads protest campers in the 1990s showed a similar resilience to evictions. Non-violent tactics deployed included lock-ons, tripods and tree-sites. At Newbury Bypass, protesters prepared eviction soundtracks and blasted music from mini-stereos strung around their necks. Humour and playfulness accompanied these evictions. As one protest camper recalls of the eviction at Claremont Road, “people’s determination and humor had maintained their spirits.”

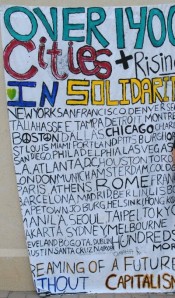

A similar spirit of creativity and commitment fills the square outside St. Paul’s Cathedral. As the possibility of an eviction looms, authorities would be wise to note the age-old saying that “What doesn’t break us, makes us stronger.” Evictions in the US have already resulted in a larger and more directed movement, with disbanded camps rebuilding often within hours. Likewise, if an eviction is scheduled against non-violent protesters outside St. Paul’s, we may see this camp turn from a space of resistance into a space of resilience.

Yet concern should resound over Dr. Fraser’s premonition of violence on the steps of St. Paul’s. For this to come true it would mean yet another show of brutal force by the police against non-violent protesters. Experiencing and witnessing police brutality breeds distrust and justifies anger. It leads to the dangerous and unnecessary deployment of police weaponry, as seen with Tasers at Dale Farm. It leads to IPCC inquests and High Court rulings against illegal police activity. It has no place in a real democracy.

This is why the people of Tahrir Square send forewarning in their solidarity letter to the Occupy Movement: “If the state had given up immediately we would have been overjoyed, but as they sought to abuse us, beat us, kill us, we knew that there was no other option than to fight back.”

–Anna Feigenbaum