How might activist-art be supported rather than undermined by the visibility and space offered by contemporary cultural institutions? Reporting on the Truth is Concrete festival in Graz, Austria, guest blogger Gavin Grindon looks at recent trends that bring protest camp structures into the art world.

Stuttgart21 Protest Camp by German photographers Frank Bayh & Steff Rosenberger-Ochs

Since late 2011, the cultural capital of protest camps has risen rapidly. One of the places this has been both reflected and reproduced is in the art world, with a wave of adoptions and appropriations of the visual and material culture of recent movements, and especially of protest camps, in exhibitions and biennales. While this de-marginalisation of what Yates McKee has recently framed as the “aesthetic techniques”[i] of social movements is to be welcomed, it raises the central question of how these techniques are transformed by being placed in this frame: not only in the particular incidence of some object or image appearing and the familiar discussion about ‘recuperation’ which might follow, but in how this appearance on centre stage impacts upon the ongoing working of these techniques outside this context, and the demarcation of what is legible as the field of ‘the political’ more generally.

This adoption of the material and visual culture of protest camps has occurred in the context of several related trends; the growing vogue in contemporary art for participatory and socially-engaged art practices, particularly those which make broad political claims or utopian promises[ii]; at the level of cultural policy, the tendency for biennales and large exhibitions to geographically shadow international governmental gatherings (and their accompanying summit-camp protests), drawing on and adding to the claims often made for these temporarily composed city-sites as spaces of democratic debate;[iii] and lastly the contemporary art vogue, associated with both these tendencies, for embracing political art, especially extra-institutional or ‘activist-art’ work. This tendency is evidenced by, for example, the 2008 Taipei Biennale or the 2009 Istanbul Biennale as well as many other smaller shows over the last few years.

This blog post is written, over the sixth and seventh days of Truth is Concrete, part of the Steirischer Herbst arts festival in Graz, Austria and focuses on both this use of camps in contemporary art, as well as on the debate this opens about the potential conflicts and agreements between the strategies of social movements, activist-art and cultural institutions.[iv]

This blog post is written, over the sixth and seventh days of Truth is Concrete, part of the Steirischer Herbst arts festival in Graz, Austria and focuses on both this use of camps in contemporary art, as well as on the debate this opens about the potential conflicts and agreements between the strategies of social movements, activist-art and cultural institutions.[iv]

Camping within exhibitions has taken several different forms in this period.[v] In late 2011, during the ambitiously titled exhibition DADA New York II: The Revolution to Smash Capitalism at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, the small number of local Occupy protestors were permitted to use the gallery as a space to shelter from the unforgiving weather, and set up camp inside. Far more ambiguous, the 2012 Berlin Biennale gave over its ground floor space not specifically to local activist groups but to international invited representatives of Occupy camps. The bottom floor of the Biennale became a semi-autonomous space in which a functioning camp was observed by gallery visitors, who were invited to join discussions. From movements, there were both sincere attempts to make use of this space as a opportunity for global networking between occupy camps and calls to refuse the paradoxical invitation to occupy, or to attempt to exceed and expose the limits of the invitation.[vi] This latter critique is founded on the solid and longstanding experience of the mistreatment of movements in their representation in contemporary art and media, but also exhibited a tendency to essentialise a recuperated ‘inside’ and a radical ‘outside’ which offered a narrow conception of the spaces and forms of social change which made invisible the potentials, as well as the pitfalls, of such an opportunity.[vii]

Its reception within the art world exhibited a not-dissimilar but typically even more simplistic and abstract conception of political possibility.[viii] Given the combination of the agitational tone of the biennale’s announcements, which attacked much of the art world’s pretentions to political agency and called instead for a turn to use-value – and the act of placing some of this broadly ‘interventionist’ work in a context of international art tourism which has previously mostly neglected and derided them – the slew of negative reviews were to be expected. This isn’t the place for an extended critique of the hopeless critical impoverishment which regularly underlies the vacuous conceptual shitstorm of contemporary art criticism’s approach to political engagement. But what became repeatedly clear is that the narrow critical terms with which the work was approached, many of the practices supported were all but illegible to these critics as art (one common criticism was that there was nothing to look at). When it came to the camp, one of the most common readings was that Artur Zmijewski, one of the curators, had placed Occupy in the space as an egomaniacal move which made the camp part of his own artwork. His previous work had typically put controversial or subaltern social groups in awkward or ironic positions.

Judith Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure

However, this reading was deeply sexist in so far as it was only possible if one remained wilfully blind to the work of his less-well known and female co-curator Joanna Warsza. In either case of its art-world or social movement-world reception, what was inevitably highlighted were the limits of the form of an art exhibition to work with both social movement forms and art which attempted to take a productivist turn towards such forms. One of the more interesting critical responses to the exhibition, in Afterall, recalled for me Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure when it argued that the reasons for these confusions lay in the fact that this biennale indeed failed to function as a well-oiled viewing machine for processing art tourists precisely because it was oriented differently and trying to achieve something else. It was a biennale, but it was not an exhibition: “the building was less an exhibition space in the conventional sense than an incubator, encampment…”[ix]

My own, albeit fleeting, experience of this space was that there were several problems with this invitation to occupy. Certainly there was a curatorial problem in the assertion of autonomy for the camp, and the inevitable limits which were to be placed on it. However, in Berlin the main problem seemed to be with the camp itself and its response to the space. I was only a brief visitor, so these are only my impressions rather than a participant or fully-grounded account of events, which might reveal a different story. My impression, however, was that the camp had responded to the space of a biennale by understanding itself as in exhibition, as on show. The occupiers used the space to start making art. There were several installations, some using video, around one side of the camp. There was also an intense profusion of banner-making and sloganeering wall-painting and graffiti. However, most of it appeared to be an ostentatious performance of political identity, made up not of either specific social demands or new poetic slogans, but assertions of identity and behavioural injunctions. The result was not only some rather ugly banners by the standards of many recent protest banner making, but some embarrassing and awkward lowest common denominator sloganeering, whose broad and nebulous claims sometimes seemed like a caricature of ‘activist’ identity. In only understanding the space as an exhibition, and not in fact as a camp, the occupiers seemed to in fact play into their critics’ hands, and rush headlong towards the kind of discomfort and antagonism created by the collision of ossified identities one finds in Zmijewski’s art. In terms of the potential uses of the space, it seemed like a missed opportunity. Rather it provided not so much a functioning project-space as an impetus to critique how the pairing an art institution and activist projects such as protest camps might relate to or transform each other.

This all brings me to where I’m sitting now, several months later, not at an exhibition but at a cultural festival, Truth is Concrete in Graz, Austria. The event has some curatorial overlap with the Berlin Biennale, but explicitly takes a different organisational form. A 24/7 ‘marathon camp,’ in which a mixture of screenings, performances, workshops and presentations, and an open stream of impromptu events occur at all times, day and night for a week. However the number of formal lecture-style presentations debilitatingly outweighs other formats and brings it closer to something like Creative Time’s ‘summits’ in New York. The model of a durational camp seems to borrow its model from Occupy camps. But the intensive and exhausting model of a marathon, aside from its competitive associations, seems an awkward match for a productive space of critical reflection and convivial collaboration. The event also, crucially, describes itself as a camp, with invited participants (myself included) put up in dorm-style rooms on site in order to participate in events, and with daily general assemblies.

This transposition of an activist organisational form, most recently associated with occupy camps, into a cultural festival is a problematic move. Such assemblies emerged as a part of social movement strategy with a specific function, addressing in radically democratic fashion what is to be done, whether organising a direct action or fixing the compost toilets in the camp. In the festival, this bottom-up strategy is turned upon its head and returned as a top-down cultural policy strategy. Decisions about events, from timetabling and food distribution to general critical orientation have already been decided by the curatorial team. The GA instead becomes a managerial ‘feedback loop,’ a space for complaint or perhaps some responsive debate, but not for organisational decisions or structural change. Its strategic function had fundamentally changed, and became one determined by the structure of inviting groups together as part of an annual cultural ‘show’ rather than by those groups wilfully collaborating for their own strategic reasons.

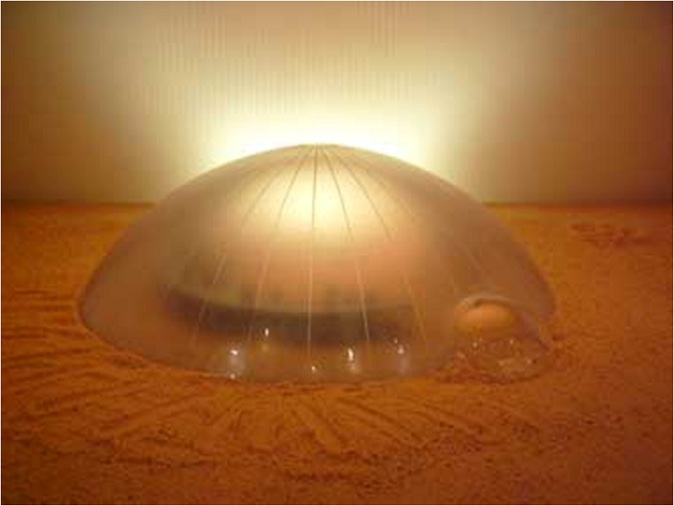

This shift is also partly a problem of Occupy movements themselves, in so far as they tended to fetishise the GA model, and turn it not only into an all-purpose solution but primarily into a space for debate and discussion over and above its organisational role. The inspiration may have been close to the idea of 123Occupy’s temporary architecture project for a ‘pop up’ inflatable general assembly,[x] but its end result was closer to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk and architect Gesa Mueller von der Haegen’s bitterly ironic suggestion for an inflatable pneumatic parliament that could be airdropped onto countries with a ‘democratic deficit’ in order to supply instant democracy.[xi]

This strategic disjunction was embodied in one image. Burak Arikan had produced a map of social movement strategies for the Berlin Biennale which was reproduced for this event, using data analysis to connect words such as ‘appropriation’, ‘documentation’ or ‘humour’ in participants’ accounts of their work, with common phrases printed as central nodes in larger type. On the opposite wall, the same approach was applied to the network of names involved (though these were only official speakers– those invited to stay and make up the camp remained invisible. Speakers were also geographically separated, with hotel accommodation outside the camp. Likewise on the event’s website speakers and ‘grant holders’ were listed separately). With some participants appearing in huge text, with connections to all the others, and others in smaller type, this was not a movement of shared political strategies, but a map of cultural capital in action. A few days in, a cheeky vandal added ‘Karl Marx’ in the bottom left corner in tiny type, with no connection to anyone on the map.

This seems quite a strong critique, but it is a critique of only one part of the festival. It is also offered in the spirit of trial and error which I found in Berlin. The question seems to be how activist-art, aligned with movement strategy, might be supported rather than undermined by the visibility and space offered by contemporary cultural institutions? As they are, such institutions are not often geared either organisationally or intellectually to a productive engagement.

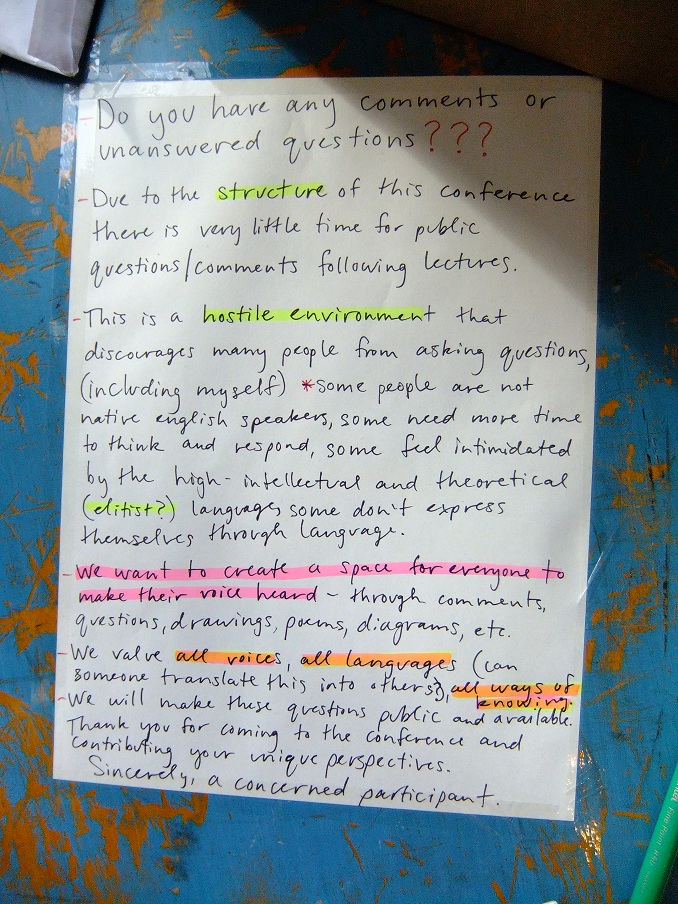

Over the first few days, with this dynamic in place, frustration seemed to grow among many participants – especially those who were used to being active. I undertook a radio project with Anja Kanngieser titled ‘What Moves Us?’ which took the form of an inquiry into the composition of the event. Interviewing participants separately, there were common responses that they felt blocked or frustrated, that “something needs to happen.” The preponderance of the lecture format, often with no time for questions or open debate, and given overwhelmingly by white male figures, became oppressive as video and audio of the talks were live streamed into the cafe. Even when eating dinner or having a drink, the drone of male voices continued to be piped in over one’s convivial discussions with others.

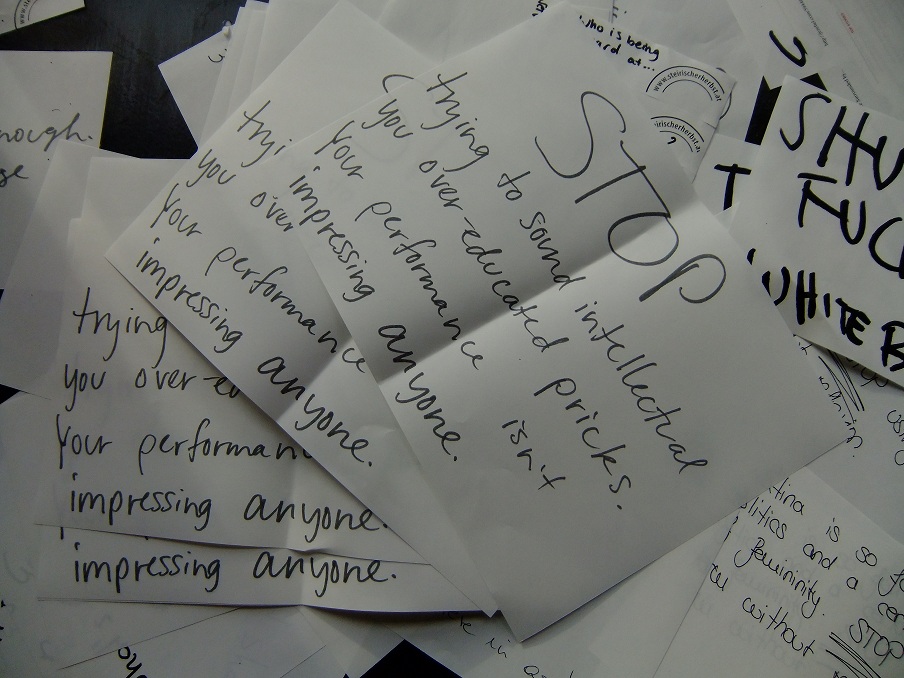

By the third day, the space had been covered in more or less coherent hand-made signs exhorting one to ‘shut up, white boy,’ or berating the speakers for the overuse of elitist academic and theoretical language that covered up more than it explained. I also heard responses in the other direction, which complained about the imagined ‘anti-intellectualism’ of these complaints. My own response in this case was that what was being asked for was actually a more sophisticated intellectual engagement, grounded and interrogable rather than evasively abstract. One other speaker even suggested that his job was to create new ideas for ‘activists’ to use, apparently intimating that they should stop complaining and get to work lugging his excellent concepts around the city, which prompted a sharp discussion about where radical theoretical ideas actually come from and what kind of use they have.

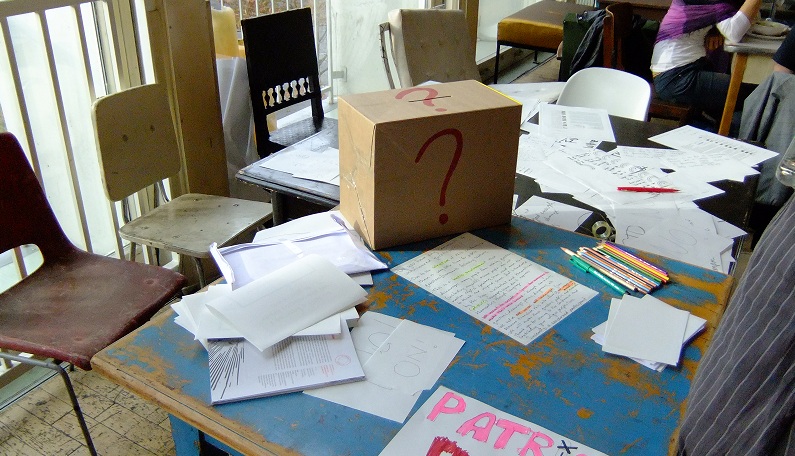

Later in the day, a feminist working group placed a message box in the bar area, outlining a series of criticisms of the lack of participation and asking for suggestions on changes which they could collectively propose to the organisers in the next GA. Later, the GA – or a large part of it – left the main GA to head outside the building and meet instead with local activists who were camping nearby. The next day, the GA left for an action within the Kunstmuseum directed against its sponsors, involving an exorcism from Reverend Billy and his choir, the spilling of ‘oil’ characteristic of Liberate Tate and a few smoke bombs. [xii]

As actions go it had clearly been a little rushed in its conception and organisation, but this was a kind of open, experimental learning grounded in embodied, practical collaboration rather than debate or theoretical discussion. Changes were evident in the format of discussions, too, as some speakers moved from the stage to the floor and began talks announcing that they were happy to be interrupted at any point for questions or requests for clarifications, and tended to give more time for discussion rather than presentation. On the Thursday, participation in the GA seemed to dissolve and Dmitry Vilensky of Russian collective Chto Delat, asked to facilitate, instead suggested that what they had was a different sort of forum which deserved another name.

From the mixture of support and fear from the curatorial team regarding rumours of an actual action occurring, it seems there were also strategic conflicts at an internal organisational level, but the vision of those within the team who did push for a more genuine engagement is deeply heartening among the other stories one hears of the depressing lack of curatorial backbone and honest intellectual engagement when dealing with activist-art.[xiii] With two days to go, it seems inappropriate to try and summarise just yet as much as the vision of the event is laudatory in so far as it attempts not to simply ‘show’ the new vogue for activist-art as a means to accumulate cultural capital, but makes some effort to intellectually and ethically engage with it in terms of the strategies from which it emerges.[xiv] But there is much work to be done.

Gavin Grindon is research fellow in Visual and Material Culture at Kingston University of London. He has published articles in The Oxford Art Journal, Third Text and The Journal of Aesthetics and Protest and has been involved in a number of activist-art collectives. You can read his writing at www.gavingrindon.net

[i] Yates McKee, “Eyes and Ears” in Michel Fehrer, ed. NonGovernmental Politics, Zone, 2007. See also his forthcoming Sensible Politics.

[ii] On this utopianism, see TJ Demos “Is Another World Possible?: The Politics of Utopia Recent Exhibition Practice” in Gavin Grindon, ed. Art, Production and Social Movement, Autonomedia/Minor Compositions (forthcoming), as well as Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells, Verso, 2012.

[iii] See Kirsty Robertson, “Capitalist Cocktails and Moscow Mules,” Globalizations 8:4, 2011. pp. 473-486.

[iv] I’d also like to say thank you to Amber Hickey and Stefano Harney for reading it over and offering some really helpful comments.

[v] It would be possible to point to precedents too, from Mark Wallinger’s 2007 State Britain, recreating a camp in a gallery, to popular actions such as the occupation of the 1968 Venice biennale and Milan triennale.

[vii] A grounded reflection on the camp from a participant argues that it was a productive and worthwhile failure: http://takethesquare.net/2012/05/31/open-letter-to-the-occupybiennale-do-artificial-contexts-pervert-replication/ . For an interesting precedent to this debate, see for example the exchange between representatives of the Resistanbul anti-IMF mobilisations and art critic Brian Holmes around the 2009 Istanbul Biennale, which occurred at the same time as these mass mobilisations: www.brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/09/01/istanbul-biennial

[viii] There are numerous examples, but typical of the tone is http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Berlin-Biennale-branded-a-disaster/

[x] They suggest several designs, with assembly instructions at www.123occupy.com

[xi] See Sloterdijk’scontribution to Latour and Wiebel (eds) Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, MIT Press, 2005.

[xii] One early media report of this action can be found here: http://derstandard.at/1348284147023/Aktivisten-protestieren-gegen-Banken-und-Industrie

[xiii] http://www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/article/on-refusing-to-pretend-to-do-politics-in-a-museum-by-john-jordan-2010

[xiv] On these potential conflicts and collusions of interest, see Amber Hickey’s Strategies for Hosting Art Activists: A Guide for Arts Institutions, available at http://www.amberhickey.com/docs/StrategiesforHostingArtActivists_Hickey.pdf

Pingback: Protest Camps and White Cubes – Gavin Grindon

Pingback: Together, What Can We Do? – Gavin Grindon